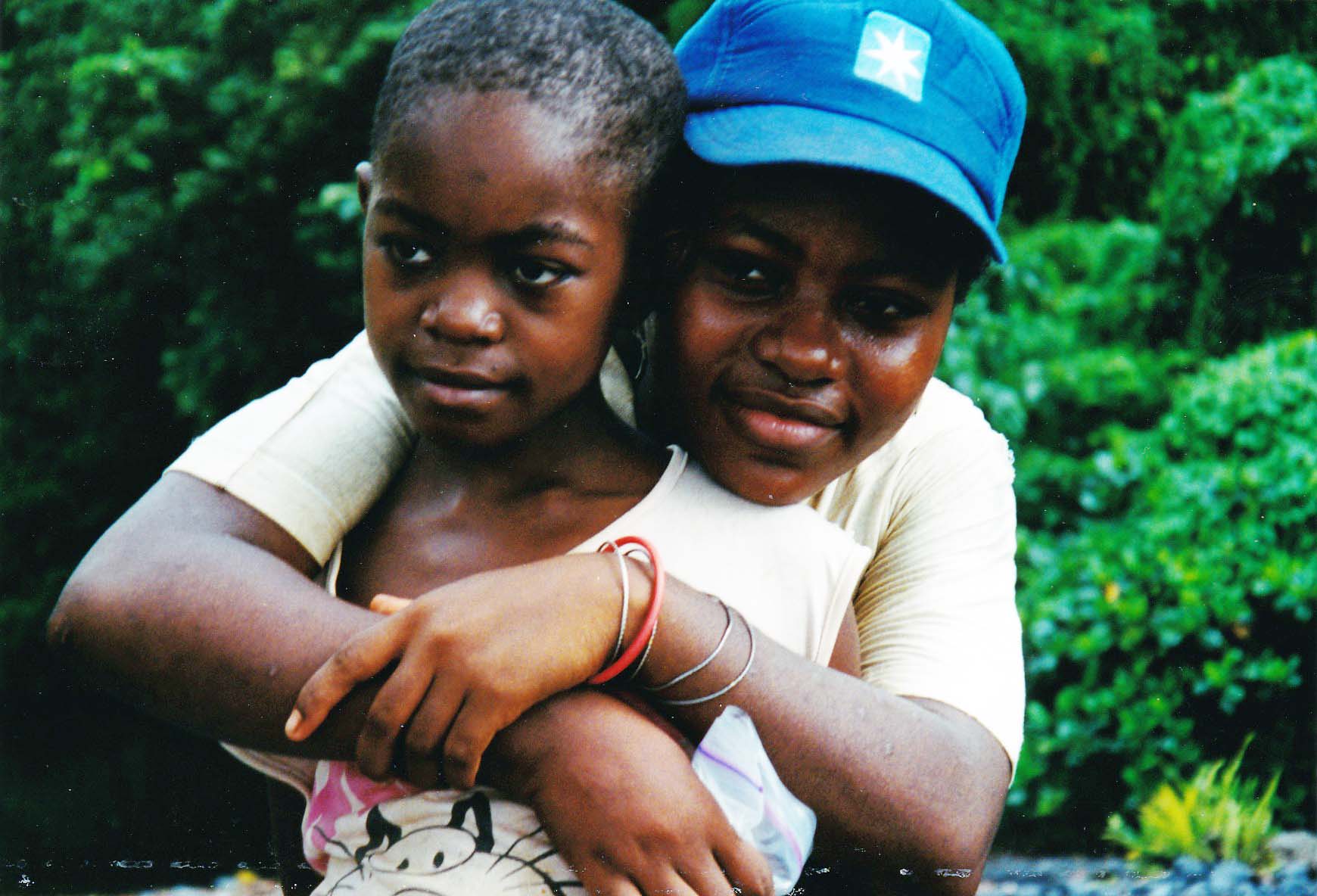

Children from Ureca, one of the earliest Bubi settlements. (Truelsen photo)

Children from Ureca, one of the earliest Bubi settlements. (Truelsen photo)

Chapter 49: Maternal solicitude

We have noted repeated times that it is the general belief among Bubis that all occurrences in this sublunar world, even the least important, fall under the beneficial or maleficent influence of spirits. Because of this belief, all of their religious practices come down to winning the favor of good spirits to protect them from the perverse influence of the reprobate. These cautious measures they take from the time a human being begins in the maternal womb.

As soon as a woman knows she is to be a mother, her first charge is to present herself to the bojiammó. He will ascertain which of her family’s deceased bought from God the soul of the creature that she feels in her womb. Once the buyer is identified, she must build a little chapel to this child’s protector or patron spirit.

The name bopiammó, although its original meaning was adorer of the spirits, has other overlapping meanings such as possessed by spirits, possessed by the devil, witch, sorcerer, etc., inasmuch as they believe themselves to have a pact and intimate relationship with the beings of the other world. They boast of it and that a bojula (pure spirit) lives in their own head, from which they obtain personal intercession and consecration. This is called bojulera lera, mojulera and also o jura mmó: to be inspired or possessed of the spirit.

During her pregnancy the mother will meticulously clean and adorn the small chapel dedicated to the spirit owner of the small child. She will burn a sacred fire that she will look after feeding while her interesting state lasts. In a corner of the small chapel she will place a clay vessel surrounded by small sticks (ribaddobaddo), which she will fill with sea water. She will sacrifice a rooster and with its blood sprinkle herself and the entrance and walls of the rojia. She will hang the head of the victim with a small bundle of his feathers on the roof, and from time to time she will cook in the sacred fire a stew of lojiri, lonay, loney or lokaba (a fruit somewhat similar to the tomato) and fish or snails (ntochi). This stew must be cooked in sea water, not fresh water.

She will adorn herself with different amulets, such as a skeleton of a nonvenomous snake (botebebe), knuckle bones of antelope (sipolo, sibolo), a strip of skin from the aforementioned snake, and a calabash neck, along with the tip of a sheep’s tail. Surrounding her waist will be a strip of goat hide to which she will attach a fruit from a climbing plant called isoba, and in the absence of the goat hide, she will wear one from a venomous snake (bebila or mebila).

On designated days she is required to cover her abdomen with a large goat skin that it is the custom of the bojiammó to keep for these cases. The most distinguished old woman will anoint her abdomen with ntola, and, in its absence, with palm oil and she will offer to the bojiammó, from time to time, a calabash of palm wine mixed with the fruit of the tupé and bark of the boale. She will carry firewood to the rojia (kom), dried skin peel of olive (ntutu, nchuchu), and dried seeds of palm (eaka), with the goal of preserving the sacred fire.

If the woman had previously suffered a miscarriage or premature birth, when again she is pregnant, occasionally she will ask the blessing of the bojiammó, so that she will give birth successfully. The bojiammó will take hold of her waist with both hands, passing them softly from the back to the front, on top of the groin, for three times, saying: Elé baribó, olo bola e sokobo: “Do not permit, oh spirit, that the infant be abortive.” This blessing they call O boa o buela bo boaiso ennabio: “To bring the womb along.” It is of relevance to note that the Bubi woman submitted herself to these ceremonies with the sole purpose and natural desire to procreate robust children. The greatest ambition of the Bubi is to have hearty and numerous progeny. It was because of this that fertility, in antiquity, was so esteemed, honored and reputed as a gift from the ancestors and so much more dear and appreciated was a husband with greater fertility. To them were completely unknown the perversions and crimes against procreation and nature. Sterility was judged as the greatest disgrace, dishonor, and a curse from the ancestors.

She who gave birth to twins was congratulated and received well wishes from neighbors, relatives, and friends. She was held in grand honor and given compliments and gifts of lambs, small goats, and chickens for this outstanding gift received from the souls of the ancestors.

During postpartum, the mother ate only a broth of herbs called bileppa, fish, and snails. The husband and friends left to go hunting, and with that hunt they celebrated a family feast in honor and thanksgiving to the mmo oró bola, the spirit who bought the infant. After a week, they had another family festival, with which they solemnized the infant’s leaving the house (lopuri lo bóla) and they gave a name to the child. The name ordinarily was the name of the spirit patron who they supposed had bought the child.

When the child turned five years old, he was subjected to the cruel torment of his barbaric and savage tattoo, of which we have already spoken. Thanks to God this bloody custom has ceased to exist.

At puberty, a young man had to sacrifice to his spirit patron a goat in thanksgiving of having been conserved healthy and robust until then and in requesting a happy, long life and virile power to produce many vigorous children. The blood of the sacrificed is placed in a piece of calabash. Some of it is scattered in the rojia, and the rest is spread on the shoulders, chest, back, and knees of the offerer (o uter’ a bannobio.)

The victim was butchered and cooked in the same sacred fire in the rojia and also eaten there.

From this moment the adolescent is treated as an adult and allowed to attend general assemblies.

The first fruits of his work he will present to the spirit in his rojia, where he will cook and eat them. The first wine of his palm trees he will put in the epanchi (small pot of clay) situated in a corner, and there it will stay until it evaporates or the insects have consumed it.

In all the troubled times and critical moments of his life, the Bubi goes to his small chapel. With sea water kept in the epanchi, daily he will wet his forehead, shoulders, stomach, and knees. There they will put him in serious illness and there he will almost certainly die.